Un autre automne à Québec. Construction everywhere. A white disc of sun presses through, like a light bulb behind a dirty sheet. Fog. But on days ensoleillé, the light seems grades brighter, sharper. Because of the river?

Finally made the cruise to Grosse Île le samedi passé. A good boat provided by Croisières Coudrier. From a seat in front, to see as much as possible, I was first struck by the length of Île d'Orléans, along which we cruised for what seemed to be half the 90 minute trip. Could see the wide chutes de Montmorency in the distance, silos rising from the big farms. A river, yes, but so wide the shores seem a mirage, an illusion of land. A dream of white church spires and white birch trunks and pretty, red-roofed houses. Into the tossy slate waves that expel crests of foamy breath, nosing up, plunging down. Le fleuve nudges, slaps, at the Orléans wharf, a sudsy ring edges back and forth from a breakwater of sharp, umber rock.

The St Lawrence seaway, something every school child learns of, and now I am cruising on it, towards the wide mouth that opens to the Atlantic beyond the Gaspé I will never reach. Not on this trip. Beyond d'Orléans, at Île Madame, the water is just 10% salt. The islands in the distance float like dark cream above le fleuve, another illusion, of course, but land may have seemed that unlikely to the voyagers who glimpsed it, finally, after weeks at sea. The mountains to the north, cloud shadows changing shape over them, blue marine against a hundred shades of green and the threatening russet.

As we near Grosse Île I spot the Celtic cross that soars up from the highest rocky point. Facts channel out from the guide's microphone. From 1832 to 1873, 55.8 percent of the immigrants who stopped here were fleeing Ireland. 40-50 died every day. In 1847 alone, 5,424 deaths. So precise those numbers. It has to be only a general ancestral association that causes my eyes to wet. Same as the tears that surprised me in the archives of the National Library in Dublin. As for my family, of the little we know, there is the fact that my grandparents arrived later in the 1800's, through Ellis Island.

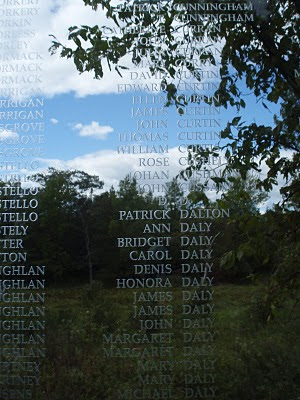

Still, along the list of names inscribed on glass at the Irish memorial above the lumpy grass beneath which coffins are stacked one upon the other, I see one Mary Curry, four Mary Ryans, ghosts with the names of my grandmothers.

Perhaps women like they were, but whose hopes typhus fever burned to nothing. I see my own name too. The young Parks Canada guide, his English words charmingly accented with Québecois, explains the famine, the failure of the potato crop, the insistence of the English landlords that tenant farmers use their oat crops to pay the rent. He talks about the doctors who fell ill trying to cure, the priests who came to administer the last rites and soon joined the crowded path from Grosse Île to the next life. The day has warmed. The guide slips off his handsome green jacket and his cap and places them on a rock. That he is sympa enough to imagine the suffering he describes is apparent as he speaks, and improbable though it is this late in the this season, a butterfly casually flutters across the space between him and his audience.

Perhaps women like they were, but whose hopes typhus fever burned to nothing. I see my own name too. The young Parks Canada guide, his English words charmingly accented with Québecois, explains the famine, the failure of the potato crop, the insistence of the English landlords that tenant farmers use their oat crops to pay the rent. He talks about the doctors who fell ill trying to cure, the priests who came to administer the last rites and soon joined the crowded path from Grosse Île to the next life. The day has warmed. The guide slips off his handsome green jacket and his cap and places them on a rock. That he is sympa enough to imagine the suffering he describes is apparent as he speaks, and improbable though it is this late in the this season, a butterfly casually flutters across the space between him and his audience.One Lazeretto still stands from 1847. Inside, a glass case holds some objects found under the building, the stained bowl of a clay pipe and a brogue of brittle brown leather, heel collar pressed down, laces lost.