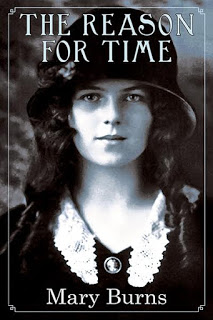

In my new book, The Reason for Time, I quote Albert Einstein, who said: "The only reason for time is so that everything doesn't happen at once." A joke, with significance, and readers will learn that it is not the only justification for the title. But another reason for time is that it encourages reflection.

About eight weeks since the book was released by Allium Press of Chicago and introduced to readers in Gibsons, Vancouver, Toronto and Chicago. Reactions have been positive, enthusiastic. How a writer itches to hear, "I loved that book...," and readers I know, and don't know, as well as early reviews have outright said or indicated just that. At a book club group of young women readers in Chicago, I was particularly touched by how they related to the main character, Maeve, who lived 100 years ago yet had some of the same problems these 30-something's have today. It was also encouraging to meet readers at Chicago's Printer's Row Literary Festival whose ancestors had stories similar to Maeve, who even lived in her old (imagined) neighbourhood.

In this increasingly categorized world of books, I'm known as a writer of literary fiction. The Reason for Time is my first, and may be my only, novel that can also be described as historical. Inspired by the pure fluid voice of Fabian Bas in The Bird Artist, by Howard Norman, and the historical sweep and narrative invention of John Dos Passos, in his U.S.A Trilogy, I hope I've achieved the truth of my character Maeve Curragh, who lived through that one crazy week in Chicago that started with a dirigible crashing into a downtown bank building and ended with the worst of 25 race riots in the "Red Summer of 1919."

Read more on Facebook, Amazon, and Goodreads.

About eight weeks since the book was released by Allium Press of Chicago and introduced to readers in Gibsons, Vancouver, Toronto and Chicago. Reactions have been positive, enthusiastic. How a writer itches to hear, "I loved that book...," and readers I know, and don't know, as well as early reviews have outright said or indicated just that. At a book club group of young women readers in Chicago, I was particularly touched by how they related to the main character, Maeve, who lived 100 years ago yet had some of the same problems these 30-something's have today. It was also encouraging to meet readers at Chicago's Printer's Row Literary Festival whose ancestors had stories similar to Maeve, who even lived in her old (imagined) neighbourhood.

In this increasingly categorized world of books, I'm known as a writer of literary fiction. The Reason for Time is my first, and may be my only, novel that can also be described as historical. Inspired by the pure fluid voice of Fabian Bas in The Bird Artist, by Howard Norman, and the historical sweep and narrative invention of John Dos Passos, in his U.S.A Trilogy, I hope I've achieved the truth of my character Maeve Curragh, who lived through that one crazy week in Chicago that started with a dirigible crashing into a downtown bank building and ended with the worst of 25 race riots in the "Red Summer of 1919."

Read more on Facebook, Amazon, and Goodreads.