My most recent Travelling Book Café featured The Reason for Time as the travelling book, and an unlikely pair, Anglican rector Clarence Li, and magician Gerardo Avila, who joined me to talk about something "we have no language for.." as Rector Li put it, magic and belief.

Early into the discussion that followed my reading, and Gerardo's performance, an audience member offered her experience of the strange, the unexplainable, as in how, as a child in England, she sang the verse: Land of the silver birch home of the beaver... long before she knew she would be living in Canada.

The magical, mysterious. What makes one person a skeptic, another a believer? My character, Maeve Curragh, works at the Chicago Magic Company, in Chicago, 1919, and comes from a superstitious rural Irish culture. She is enchanted by the vaudeville illusionists she sees on Chicago stages, but more so by the mind readers and the spiritualists, such as Anna Eva Fay, who were so popular then. A simpler time maybe? When people were more disposed to believe? Or was it just her? Because, as Clarence Li pointed out, there are personality types who are more likely to "believe." One audience member described herself as exceptionally sensitive to the supernatural. She talked about having gone on a vacation at a time when she really needed one, except, her body remained at home, in bed. The experience was so vivid she can still remember the smell of the trees at the mountain resort. It scared her.

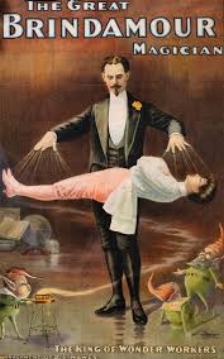

Gerardo, our magician, dressed in a dark suit and a floppy bow tie, pressed the button on his boom box and music trickled forth at just the right volume to establish a different ambiance in the library's community room. He worked with strings, balls, and cards, deftly making them disappear and re-appear. He even had a trick that was designed to convince the most unrelenting of skeptics. It's about bringing people into the present, he explained, with music, with comedy... with a sense of possibility. He performs tricks that sometimes surprise himself. Magic happens when something unexpected elevates a trick to something, well...unfathomable.

The eloquent Clarence Li doesn't think belief is anything that ultimately exists or doesn't, but that it comes and goes. It's a journey, he said, and while, as a minister, he is in the God business, he regrets the post-Enlightenment rejection of myth as fanciful. It's why we struggle to explain, why we chalk some experiences up to being just plain inexplicable; everything is quantified, must be proven. "People say seeing is believing, but for me believing is seeing." Don't worry about believing, just be, he said, echoing, if in different words, what Gerardo had said about being present.

Audience members used words like serendipity and coincidence. We talked about the power of suggestion; we talked about how people believe what they want to believe, for various reasons. We talked about trust and its cultural roots. If you come from a suspicious society, can you ever believe anything but what you can see, touch, hear, or verify by some branch of science? Do aboriginal cultures have a natural advantage over us in that department?

As we were wrapping up, the woman who forgot that, less than two hours earlier, she had opened the discussion, supplied an identical coda: "When I was a child in England, I used to sing, Land of the Silver Birch, home of the beaver, and so forth, and I never imagined I'd end up living in Canada." The repetition of the song in her flutey voice brought us full circle, as if to emphasize the mysterious ways our human minds work, sometimes according to an enigmatic logic all their own.